Code Generation

Main Source:

- Book 1 chapter 11

Helper Functions

Section titled “Helper Functions”When generating codes, it is useful to create several helper functions.

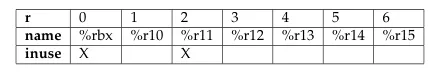

int scratch_alloc();void scratch_free( int r );const char * scratch_name( int r );These are helper functions related to registers. We will store register in a table and access them with number.

Source: Book 1 page 182

scratch_allocis used to allocate for free register, mark it as used, and return the register number.scratch_freemarks the registerras free for use.scratch_namereturn the name of register with the given numberr.

Scratch registers are also known as registers used to keep intermediate result or value.

In the assembly program, to indicate jumps and conditional branches, we will need many labels. These two function should help us in label management, including generating and retrieving them.

int label_create();const char * label_name( int label );We are going to use generic label name like L1, and it is going to be incremented as we use label_create. It’s function simply increment global counter and return current value. The label_name return label in string form given its number. label_name(15) would return ”.L15”.

Then, write a function to map between symbol in program to its assembly language representation.

const char * symbol_codegen( struct symbol *s );

It takes the symbol representation, which may contains the scope. Scope will be examined to determine whether to return the corresponding symbol in local or global scope. It should return a string which represent the instruction to compute the address of that symbol. For example, if the given symbol is local variable or function parameters, the address may be computed by doing stack instruction.

Generating Expressions

Section titled “Generating Expressions”To generate an expression, we need to traverse the AST or DAG.

The AST represents the expression’s operands in the left and right child nodes, while the operation performed on them is the parent node itself. A post-order traversal ensures that the left and right child nodes are visited first, so we know what the operands are.

The strategy is to store left and right node’s value temporarily in registers. To let the parent node know which register we used, we store an information about it in each node. On each visit to node, we should generate corresponding assembly code.

Source: Book 1 page 184

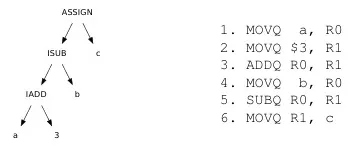

Each step correspond to each line of the assembly code.

- A post-order will visit the left-most node, which is

a. Thisawill be stored in register allocated from thescratch_alloc. It should be allocated on theR0, and the instructionMOVQ a, R0is generated. - Next, node

3is visited, and it will be allocated on theR1. Corresponding instruction is also generated. - The parent

IADDis visited. It should know that its children hold values onR0andR1. It will generateADDQ R0, R1. SinceADDis destructive that leaves result in the second argumentR1,scratch_free(R0)will be called. - The

bis visited, similarly,scratch_allocis called to allocate the registerR0. - The parent

ISUBis visited. It should compute based on registers onIADD, which stores its value inR1andb, which stores inR0. Result is stored inR1andR0is freed again. - Visit the

cnode, but this will not produce code, since it is a target assignment. - Visit the

ASSIGNnode and produceMOVQ R1, c.

We should also call scratch_name on each register to obtain the real register name.

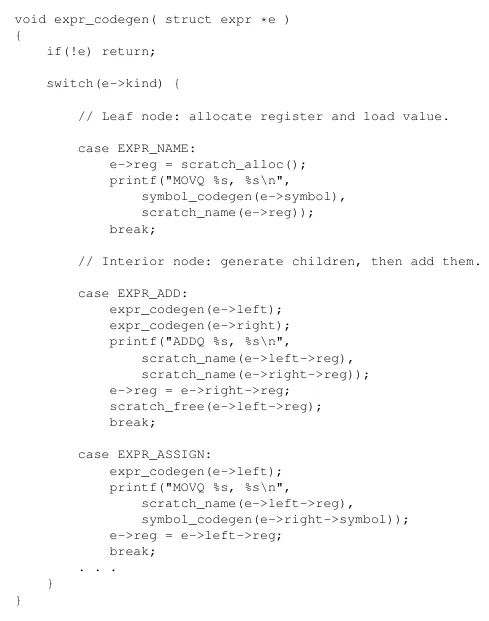

MOVQ a, %rbxMOVQ $3, %r10ADDQ %r10, %rbxMOVQ b, %rbxSUBQ %rbx, %r10MOVQ %r10, cHere is one example of how the traversal can be implemented in code:

Source: Book 1 page 186

Consider the case when variables a, b, and c were not so simple, such as a literal in function argument, or an argument that needs to be evaluated.

For example, if a is first argument of a function, this would be generated instead: MOVQ -8(%rbp), %rbx. The minus 8 indicates that we are moving the base pointer on the stack because a function first argument is located at an offset of 8 bytes below the %rbp register (in x86_64 machine).

When multiplication happens, result is always stored in %rax and its potential overflow in %rdx.

MOV $10, %rbxMOV x, %r10MOV %rbx, %raxIMUL %r10MOV %rax, %r11This mean that we can’t use %rax and %rdx during multiplication. We better not use %rdx anywhere for this purpose.

Function Call

Section titled “Function Call”

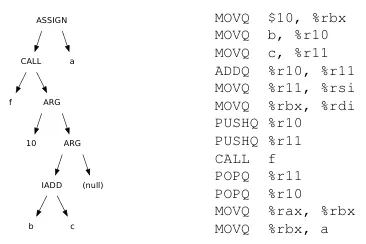

a = f(10, b + c)

Source: Book 1 page 187

When calling a function, the ARG node corresponds to a function argument. Depending on the case, function arguments may be passed by placing them on the stack or by placing them in registers. With the former (also called stack calling convention), we will use the PUSH instruction. With the latter (also called register calling convention), we should copy each of them to the argument registers. The %rdi and %rsi are typically used for first and second arguments of a function.

Before calling the function with CALL f, we have to preserve any registers used before doing this function call. Save caller-saved registers before CALL and restore them after it returns. In this case, the caller-saved registers are %r10 and %r11. They contain the value of b and c, which is computed as argument already, yet we still include them. This is because it is possible that function f depends on or modifies them, which means it causes side effects to the registers. By preserving them, we ensure that f is provided with the expected values and that the original values are restored afterwards.

The function returns value should be stored in %rax, and it will be moved to newly allocated scratch registers %rbx.

Generating Statements

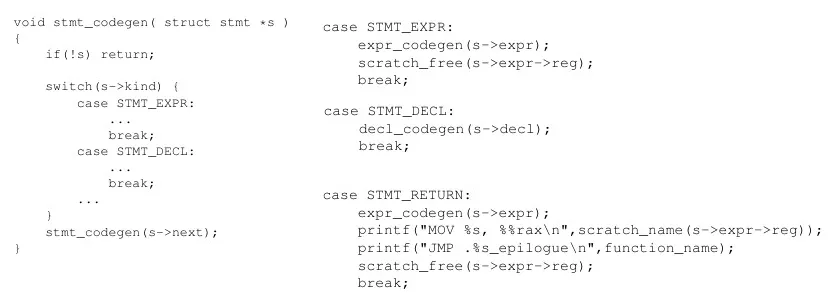

Section titled “Generating Statements”Various statements can be encountered, this includes control flow statements. We should create a function that generates code for any kind of statements. One could look like below.

Source: Book 1 page 188

Recall the AST representation of statements, all information about a statement is encapsulated in the stmt struct. The struct includes several optional fields, such as body expression, else expression (if an if statement), declaration (if a declaration).

Each statement may call another specific generator.

- A declaration is simple; it simply calls the code generator for declaration.

- A statement that includes expression will obviously need to generate expression, which can call the previously discussed

expr_codegenand free the registers used by the expression after. - A return statement must be evaluated as well, hence

expr_codegenshould be called on the given statement. After a function returns, it is expected that the execution continue to the caller. In other word, we must jump to the return address on the call stack.

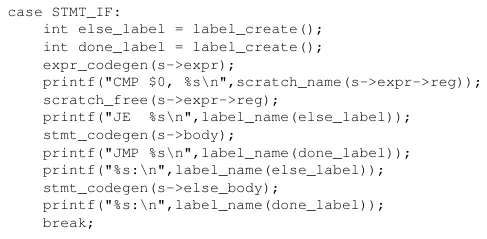

Control Flow

Section titled “Control Flow”A control flow like if-else statement should look like:

if (expr) { true-statement} else { false-statement}The approach is to evaluate the expression first, then use CMP to evaluate to true or false. Depending on the result, jump to the corresponding statement.

The assembly should be like below.

exprCMP $0, registerJE false-labeltrue-statementJMP done-label

false-label: false-statement

done-label: ...next codeIt evaluates expression, compares whether it is 0 (false). If it’s a yes, jump to false-label, which contains the false statement. Else, the true statement will be evaluated, and once it is done, skip the false-label by jumping directly to the next code (done-label).

Source: Book 1 page 190

A for loop is:

for (init-expr; expr; next-expr) { body-statement}In assembly:

init-exprtop-label: epxr CMP $0, register JE done-label body-statement next-expression JMP top-labeldone-label: ...next codeThe initialization expression should be evaluated first. A typical loop is constructed by:

- Compare result of an expression.

- Depending on the result, either execute the body statement, execute next expression (e.g., increment counter), then jump back to the start of the loop, or jump to the next code.

Conditional Expressions

Section titled “Conditional Expressions”Conditional expression includes comparison between data types that returns boolean values. They can be less than, greater than, equal, etc. It is a form of left-expr < right-expr. If we assign the result of comparison to a variable, such as b: boolean = x < y;.

left-expr right-expr CMP left-register, right-register JLT true-label MOV false, result-register JMP done-labeltrue-label: MOV true, result-registerdone-label: ...next codeLeft and right expression is evaluated. Both results are stored on their corresponding register. CMP is performed on the two, which set the register flag. Depending on the result, it can execute the JLT (jump if less than) to the true-label, which assign true to the result register, or execute the MOV false, result-register, which assign false instead.

Generating Declarations

Section titled “Generating Declarations”Declarations can be local variable declaration, global variable, and function declaration. Global declaration is simple, we just need to generate label on the data section of the assembly code.

i: integer = 10;s: string = "hello";b: array [4] boolean = {true, false, true, false};.datai: .quad 10s: .string "hello"b: .quad 1, 0, 1, 0If there were conflicting declaration, the further declaration will overwrite the previous values. If the declaration contains expression, they will need to be evaluated first, because data section must contain constant values.

A local variable declaration is contained within a function. This mean that it is pushed onto the stack during the function execution.

To declare a function, we will need to generate label for the function name to start executing the function, and another label for the return statement. Inside the function, we will need to do necessary steps, this includes the function prologue and epilogue.

- Prologue: Setting up function’s stack frame, including allocating space for parameters and local variables.

- Epilogue: Cleaning up the function’s stack frame before returning, such as restoring the stack pointer, restoring the previous base pointer.

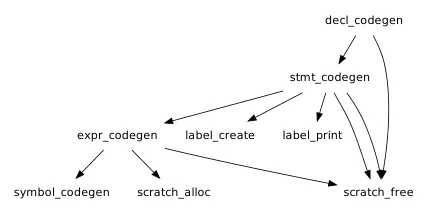

Overall, the relationship of the code generator functions can be summarized as follows.

Source: Book 1 page 182