Syntax

Main Source:

- Book 2 chapter 2

- Backus-Naur form — Wikipedia

Syntax is the rules that specifies the valid structure of a program. It defines how the elements of a programming language, such as keywords, identifiers, operators, expressions, and statements can be combined to form well-formed programs. The structure of program need to be standardized in order to avoid ambiguity. By ambiguity, we mean situations where a given sequence of symbols can be interpreted in multiple ways, leading to different meanings or interpretations.

An example of ambiguity can be illustrated with simple arithmetic expression: 2 + 3 × 4. This can either be interpreted as 2 + 3 then × 4, if the language always process anything from left-to-right (also known as left-to-right evaluation), or 3 × 4 then + 2, if the language follows typical math operations.

Basic Syntax

Section titled “Basic Syntax”One way to represent a syntax is through a non-terminal symbols, then using production rules to define how these non-terminal symbols can be expanded. Example:

digit -> 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 , this mean digit is a non-terminal that can be expanded to either 0, 1, 2, and so on until 9. The | represent “or”.

A non-terminal symbol represents a syntactic category or a language construct in a grammar. In English language, non-terminals are general term like sentence, noun, verb, or phrase. There is also terminal symbol which represent the actual elements or words in the language. For example, the word “cat” is a terminal that belongs to noun non-terminal. The grammar rule for noun would be noun -> cat | dog | tree | ....

A syntax rule for any number greater than 100 would be:

<greater-than-100> -> <non-zero-digit> <digit> <digit> <digit>*<non-zero-digit> -> 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9<digit> -> 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9A number greater than 100 must be anything beyond 100, like 101, 102, 103, and so on. So, the first digit should be any digit that is non-zero. We should add another rule <non-zero-digit> for this. Then, the non-zero digit is followed by two digits, signifying it must be followed by two digit, so number like 99 is invalid according to this syntax.

After the two digit, there is another digit included with the * symbol. This corresponds to Kleene star operator, which mean the particular non-terminal can be repeated zero or more times. A single <digit> with Kleene star means we can put any digit as many as we want. So, it is possible to create long number like 10000000000 or 123123123 with this syntax.

Regular Expression

Section titled “Regular Expression”A regular expression is a pattern or rule that is used to describe valid strings or sequences of characters within a language. If syntax defines the overall structure and grammar of a language, regular expression is the notation for pattern matching and string manipulation.

Syntax are built on tokens, which are the smallest individual units or elements in a programming language. They represent predefined categories of lexical elements, such as keywords, identifiers, literals, operators, and punctuation symbols.

For example, the symbol +, -, *, and / are mostly literals in most programming languages for arithmetic operation. Keyword like while, if, and else are also common for defining control flow.

Regular expression is a formal rule to define tokens, some rules are:

- Character: Must contain character or symbol that specify the pattern.

- Empty String: Empty string is represented with or epsilon symbol.

- Concatenation: Runs under three operation, concatenation, alternation, and repetition. Concatenation specifies that two patterns must appear consecutively in the input string. For example, if there are two regular expressions, and , the concatenation of and : means that must be followed by in the input string.

- Alternation: The “or”, represented by the

|symbol is called alternation. It allows for multiple choices at a particular point in the syntax. For example, if there are two regular expressions, and , means that either or is valid at that position in the input string. - Repetition: Specifies how many times a pattern can occur. Common quantifiers include for zero or more repetition, or , for one or more repetition.

With regular expression, we can represent an integer:

<integer> -> (- | ε) <digit> <digit>\*<digit> -> 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9The (- | ε) specify that we can either put negative sign or nothing before the first digit.

Context-Free Grammar

Section titled “Context-Free Grammar”While regular expression can represent tokens, they have limitations when it comes to handling nested constructs. A nested construct refers to a structure or element that is contained within another similar structure or element.

Regular expression won’t be able to do this:

<expr> -> (<expr> 0 | ε)This syntax defines that an expression can be expanded to another expression followed with a “0” symbol. Furthermore, that expression can be expanded again, as many as we want, creating a recursive production rule. At the point we want to stop expanding, we can choose to expand it to empty symbol.

For example, given an <expr>, we can transform it into <expr> 0 (by changing <expr> into <expr> 0), then transform it again into <expr> 0 0, and so on.

The formal methods which can do this is called context-free grammar.

Backus-Naur Form (BNF) is a common notation to describe a syntax. A syntax described by BNF must be at least a context-free grammar, because BNF allows for recursive production rule. Typically, BNF represent a rule with:

<symbol>::= __expression__.

Any non-terminal such as symbol must be enclosed with angle brackets, and its presence in input must be replaced (indicated with ::=) with expression on the right, which can be another non-terminal that requires to be replaced as well, or just a terminal.

The use of | indicate a choice, similar to regular expression. BNF doesn’t include the * or + symbols for repetition, but they can be used in another variant of BNF called Extended Backus–Naur Form (EBNF).

Derivations & Parse Trees

Section titled “Derivations & Parse Trees”Derivation describes the step-by-step process of rewriting symbols in a grammar to generate a particular string. It shows how the grammar rules are applied to transform the start symbol into the desired string.

Each step in a derivation involves selecting a non-terminal symbol and replacing it with the right-hand side of a production rule that matches the selected non-terminal symbol.

With a rule in context-free:

<expr>::= (<expr> 0 | <expr> 1 | <expr> 2 | <expr> 3 | ε)The derivation process, starting from a single <expr> can lead to any string in the language. We can generate various strings, such as “0”, “1”, “10”, “321”, “12303”, each requiring a distinct derivation process.

Let’s say that the <expr>::= <expr> 0 is the first rule, <expr>::= <expr> 1 is the second rule, and so on. To generate the string “3210”, we will follow the first, second, third, and fourth rule, respectively. We call each string generated during the derivation process in a sentential form.

Sometimes, if the production rule produces multiple non-terminal, such as <expr>::= <expr> <expr> <0>, the derivation can go more complex. At this point, there will be two choices, expanding the leftmost <expr> first, or the second. We call a derivation process in which leftmost non-terminal is always derivated first a leftmost derivation, while the opposite is rightmost derivation.

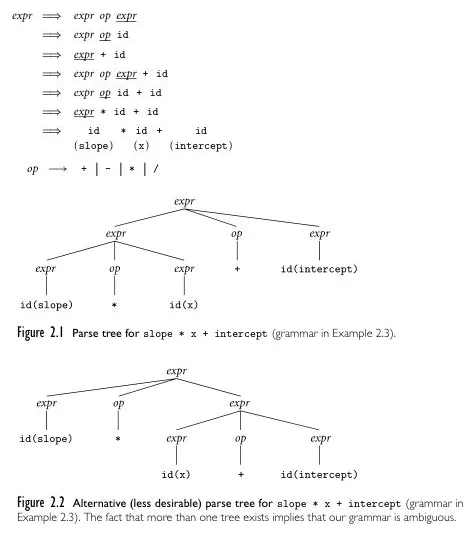

The derivation process can be represented graphically in a parse tree. Different derivation that leads to different string generates different parse tree.

Source: Book 2 page 43-44

The above is an example of a context-free grammar derivation in a parse tree. First, the expr is transformed into expr op expr, creating another two expr and an op. Then, the derivation continues, where expr is turned into some identifier, and op is turned into one of the four choice of operator.

If there are more than one parse tree generated for the same string, we can say the grammar is ambiguous. It turns out that the parse tree on the top derives leftmost expr first, while the second is the opposite. The generated string is the same, but the order of derivation is different. The first phase tree precede operator * (multiplication) before +.