Assembly Language

Main Source:

- Assembly language — Wikipedia

- Assembly Language in 100 Seconds — Fireship

- Chapter 10, Introduction to Compilers and Language Design - Douglas Thain

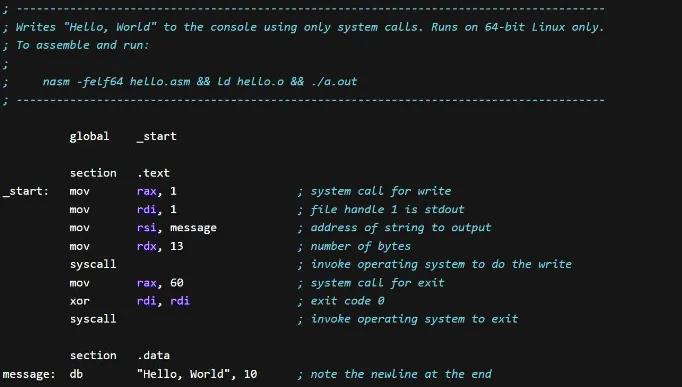

Assembly Language (asm) is a low-level programming language that is between the machine code (binary instructions understood by the computer’s hardware) and high-level programming languages (which is readable by humans). asm can be thought as a human-readable representation of machine code instructions. With asm, programmers can see the code that interacts directly with the computer’s hardware.

Due to the direct interaction with the hardware, asm is specific to a particular computer architecture or processor family. Different processors have their own assembly languages, tailored to their instruction sets, registers, and addressing modes. Therefore, code written in assembly language is not portable across different hardware platforms without modification. Similarly, this what makes one program can’t always be run in any platform, because it has to be compiled to different asm.

Source: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/assembly-language.asp

Translation to Machine Code

Section titled “Translation to Machine Code”Assembly language uses mnemonic instructions, which are short and easy to remember symbol that represent a single instruction in the machine. The instructions are then combined with operands, which are values or addresses that the instructions operate on.

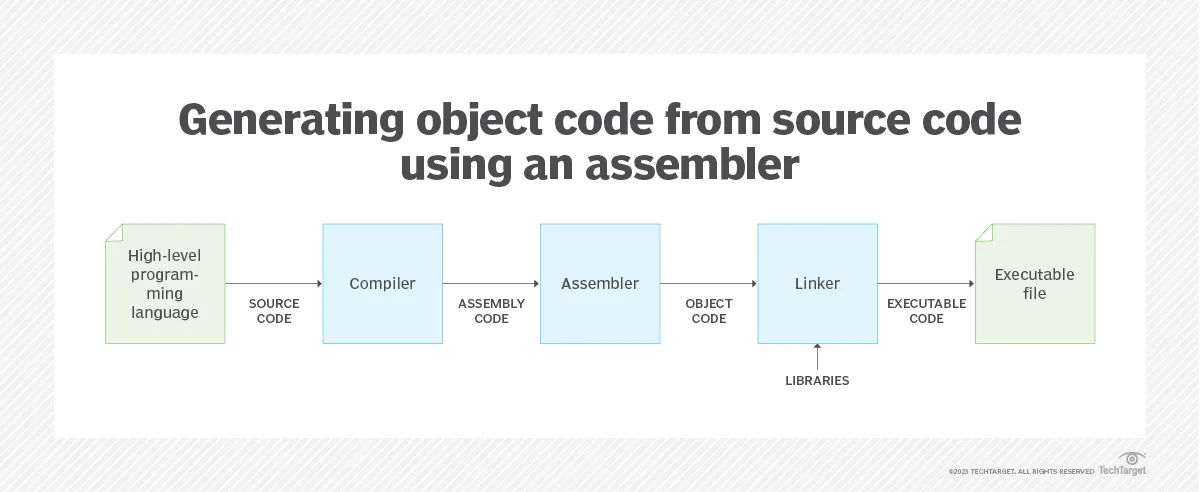

Once assembly language is written, it needs to be translated into machine code, this process is known as assembly. An assembler is used to convert the mnemonic instructions and symbolic names into the binary instructions understood by the target processor. The assembler looks up on the instruction table how the mnemonic instructions map to the binary codes. It will also perform other necessary steps, such as, calculating memory addresses, calculating constant expressions, combining the instruction with the operands, etc.

Assembly language also provide a way for programmers to define instruction that are not executed by the processor but provide instructions to the assembler, they are called directives. They help programmer to organize and control the assembly code.

Assembler translates assembly language into machine code called object files. An assembly program that depends on external source files or libraries needs to be linked together. After object file of each is produced, a linker will resolve all external references to them. It locates and loads various definition of function to create the final executable.

Example

Section titled “Example”For example, we can write instruction (or produced from compilation) like MOV AL, 61h, which instructs the processor to move the immediate value 61h (number 61 hexadecimal or 97 in decimal) to the register AX. The assembler will translate this particular instruction to binary code: 10110000 01100001.

10110is theMOVinstruction in binary.- Register

AXis identified by000. - The binary equivalent of hexadecimal

61is01100001.

Source: https://www.techtarget.com/searchdatacenter/definition/assembler

Type of Instruction

Section titled “Type of Instruction”Common type of instructions in assembly language:

- Data Movement Instructions: These instructions move or copy data between registers, memory, and I/O devices.

- Arithmetic and Logic Instructions: These instructions perform arithmetic operations such as addition, subtraction, and multiplication; and logical operations such as bitwise AND, OR, NOT, and XOR on data.

- Control Flow Instructions: These instructions control the flow of execution within a program. Examples include changing program flow with or without a condition, or jumping to specific part of program after a function finishes its execution.

- Input/Output Instructions: These instructions facilitate communication between the processor and I/O devices.

- Stack and Memory Management Instructions: These instructions manipulate the stack (pushing or popping values) and manage memory operations such as allocating and deallocating memory.

Syntax & Instructions

Section titled “Syntax & Instructions”Three elements of assembly code:

- Directives: Directives start with a dot, which indicates starting position of a section. Assembly code is divided into several sections, there are sections for code, which contains the actual logic of the program, section to declare variable and constants, and defining linker.

- Labels: End with a colon, indicating a point of interest in the program, which can be used in the code section, such as the beginning of a subroutine, a loop, or a branch target.

- Instructions: The actual assembly code, which is typically written line by line, with each line representing a single instruction.

There are many instruction keywords in asm:

-

Instructions

- MOV (Move): Copies the value from one location to another. It is used to transfer data between registers, memory locations, and immediate values.

- ADD (Addition): Performs addition between two values and stores the result.

- SUB (Subtraction): Performs subtraction between two values and stores the result.

- MUL (Multiplication): Performs multiplication between two values and stores the result.

- DIV (Division): Performs division between two values and stores the quotient.

- INC (Increment): Increments the value of a register or memory location by 1.

- DEC (Decrement): Decrements the value of a register or memory location by 1.

-

Bitwise Operations

- AND (Bitwise AND): Performs a bitwise AND operation between two values.

- OR (Bitwise OR): Performs a bitwise OR operation between two values.

- XOR (Bitwise XOR): Performs a bitwise XOR operation between two values.

-

Registers

- AX, BX, CX, DX, EBX (general-purpose registers)

- AL (accumulator low)

- EAX (extended accumulator)

- SP (stack pointer)

- BP (base pointer)

- SI (source index)

- DI (destination index)

- IP (instruction pointer)

- FLAGS (flags register)

-

Control Flow

- CMP (Compare): Compares two values and sets the flags based on the result.

- JMP (Jump): Transfers program control to a specified location in the code.

- JZ (Jump if Zero): Jumps to a specified location if the zero flag is set.

- JNZ (Jump if Not Zero): Jumps to a specified location if the zero flag is not - set.

- JE (Jump if Equal): Jumps to a specified location if the equal flag is set.

- JNE (Jump if Not Equal): Jumps to a specified location if the equal flag is not set.

- CALL (Call): Calls a subroutine or function at a specified location. This instruction actually include jumping to the function address and leaving a return address for the stack pointer to return after the subroutine is finished.

- RET (Return): Returns from a subroutine to the calling code.

-

Stack Operations

- PUSH (Push): Pushes a value onto the top of the stack.

- POP (Pop): Removes a value from the top of the stack.

-

Directives

- DB (define byte)

- DW (define word)

- DD (define doubleword)

- DQ (define quadword)

-

Data Types

- BYTE: A single byte of data

- WORD: 16-bit value or two bytes of data.

- DWORD: 32-bit value or four bytes of data.

- QWORD: 64-bit value or eight bytes of data.

Example

Section titled “Example”Example of asm code for adding two number

section .data num1 db 5 ; Define a variable called num1, which is a byte and has the value of 5 num2 db 3 ; Define a variable called num2, which is a byte and has the value of 3

section .text global _start_start: ; Load num1 into al register mov al, [num1]

; Add num2 with num1 in al add al, [num2]

; Store the result in another variable mov [result], al

; Exit the program mov eax, 1 ; System call number for exit xor ebx, ebx ; Exit status code (0 for success) int 0x80 ; Perform the system call

section .data result db 0 ; Variable to store the resultThe section .data is a section directive to define and initialize data such as variables, constants, and strings. The section .text is the section for program’s executable instructions. _start is a label that marks the entry point of the program.

x86 Assembly Language

Section titled “x86 Assembly Language”They are assembly language that represent instructions for x86 architecture, which originate from the original Intel 8086 processor.

x86 Registers

Section titled “x86 Registers”There are 16 general purpose register for the 64-bit x86 architecture.

![]()

Source: Book 1 page 152

%rax: Accumulator register%rbx: Base register%rcx: Counter register%rdx: Data register%rsi: Source index register%rdi: Destination index register%rbp: Base pointer register%rsp: Stack pointer register%r8-%r15: Additional general-purpose registers

Each register has evolved sizing from 8 bits, 16 bits, 32 bits, and 64 bits. For example %rax was known ax %eax in 32 bits.

x86 Addressing Modes

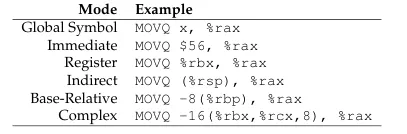

Section titled “x86 Addressing Modes”To specify the location of data operands or instructions (also known as addressing modes):

- Instruction is provided with the data types for its operand. The

MOVinstruction moves data between registers and memory.MOVB,MOVW,MOVL,MOVQ, moves byte (8 bits), word (16 bits), long (32 bits), and quadword (64 bits), respectively. - Global addressing: Operand is global value, can be a defined label.

- Immediate addressing: The operand 42 is a constant value

MOVQ %rax, 42. - Register addressing: Operand

rbxoriginate from a registerMOVQ %rax, %rbx. - Indirect addressing: Operand is indirectly located in a register by memory address, such as the stack pointer

%rsp. - Base-relative addressing: Operand is specified from an address added with constant (e.g.,

-16(%rcx), 16 bytes before%rcx). - Complex addressing: Used to address element in an array in the form of

D(Ra, Rb, C), which refers to the value at addressRa + Rb * C + D.RaandRbare general purpose registers, which gives size of the array and index of the array, respectively.Cgives the size of the items in the array andDis offset relative to that item.

Source: Book 1 page 155

x86 Arithmetic

Section titled “x86 Arithmetic”ADD and SUB adds and subtracts, respectively, both require two operands, which a source and target. For example, ADDQ %rbx, %rax adds %rbx to %rax, overwriting previous content of %rax.

More complex example can be translated into:

c = a + b + b

MOVQ a, %raxMOVQ b, %rbxADDQ %rbx, %raxADDQ %rbx, %raxMOVQ %rax, cIMUL (integer multiply) of two 64 bits integer can potentially result in 126 bits integer. To multiply, we must provide one operand in the IMUL instruction and place one operand in %rax. The lower 64 bits of the result is stored in %rax, while the higher one is placed implicitly in %rdx.

c = b * (b + a)

MOVQ a, %raxMOVQ b, %rbxADDQ %rbx, %raxIMULQ %rbxMOVQ %rax, cIDIV instruction performs division by dividing a 128-bit dividend, by a specified divisor. The low 64 bits and high 64 bits are stored in %rax and %rdx, respectively. The quotient is then stored in %rax, and the remainder is stored in %rdx.

INC and DEC increment and decrement register destructively.

a = ++b

MOVQ b, %raxINCQ %raxMOVQ %rax,bMOVQ %rax, aAND, OR, XOR perform bitwise operations on two values, while NOT performs on one value.

c = (a & ~b)

MOVQ a, %raxMOVQ b, %rbxNOTQ %rbxANDQ %rax, %rbxMOVQ %rbx, cx86 Comparisons & Jumps

Section titled “x86 Comparisons & Jumps”JMP may be used to jump between part of program. It can be used with label to create a loop:

MOVQ $0, %raxloop: INCQ %rax CMPQ $5, %rax JLE loopThis initializes %rax with the value 0. It is then incremented with INCQ and compared with the value 5 using the CMPQ instruction. If the comparison fails, it jumps back to the starting loop. Under the hood, the comparison should set internal registers (called EFLAGS) to 0 or 1, indicating the result. We don’t need to look at that register directly; it is done implicitly.

If we were to remove comparison and use JMP instead of JLE, this would result in infinite loop.

x86 Stack

Section titled “x86 Stack”Stack operation that pushes and pops element from the stack is done by manipulating the stack pointer (%rsp).

SUBQ $8, %rspMOVQ %rax, (%rsp)This is essentially pushing %rax to the stack. Stack pointer, keeping track the bottom-most item on the stack (actually the top of stack because the stack grows to bottom), is subtracted by 8 (the size of %rax in bytes), then we move content of %rax to the location pointed by the stack pointer.

Popping a value is kind of the reverse process.

MOVQ (%rsp), %raxADDQ $8, %rspBoth operation is frequently used that they have their own instructions, namely PUSH and POP.

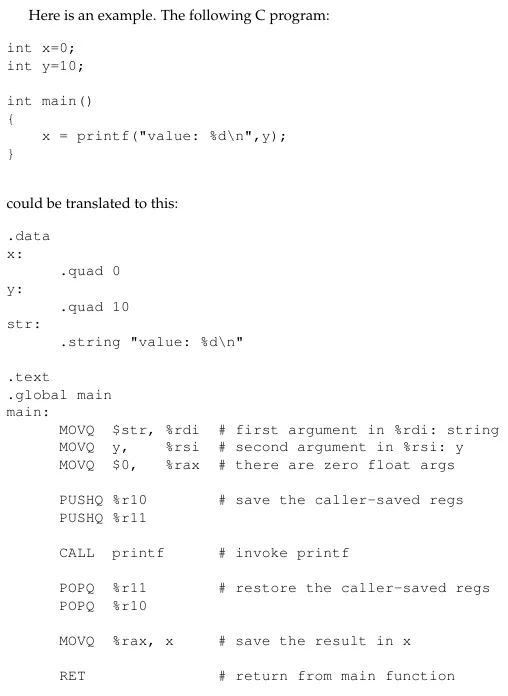

x86 Calling Function

Section titled “x86 Calling Function”A function can be called with the CALL instruction. Under the hood, it pushes the current instruction pointer (return address) onto the stack, then jump to the code location of the function. Also, we need to place the function arguments (as well as evaluate them) in some specified registers, this is same for the return value.

Registers need to be preserved and restored across function call. Depending on the language, it can either be the caller or the callee that saves the value. See calling sequences.

Source: Book 1 page 161

ARM Assembly Language

Section titled “ARM Assembly Language”The ARM assembly starts from 32 bits. It is based on RISC, rather than x86 which is based on CISC.

ARM Registers

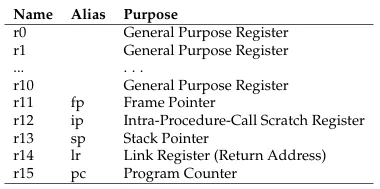

Section titled “ARM Registers”ARM-32 has 16 general purposes registers, named from r0 to r15.

Source: Book 1 page 167

There are additional registers which can’t be accessed directly, namely Current Program Status Register (CPSR) and Saved Program Status Register (SPSR). They are used to store processor’s status and control information, such as the result of comparison instruction.

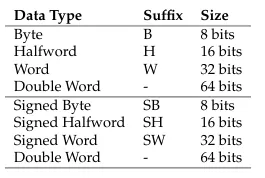

Data types in ARM:

Source: Book 1 page 168

ARM Addressing Modes

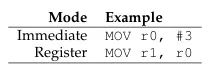

Section titled “ARM Addressing Modes”ARM separates instruction to copy data between registers and between registers and memory. MOV can be used to copy data and constants between register, LDR (load) and STR (store), to move data between registers and memory.

This is an example of moving data between registers using MOV. Immediate value is denoted with #, and they must be lower than 16 bits, else LDR should be used. ARM places destination register on the left, while source is on the right (except for STR).

Source: Book 1 page 168

- Move value 3 to register r0.

- Move value of register r0 to register r1.

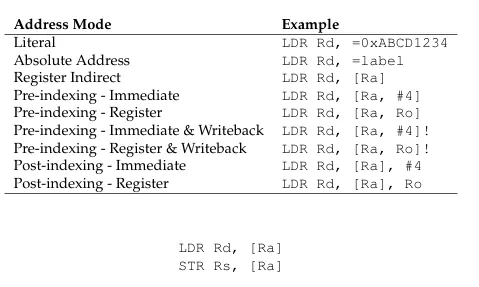

Source: Book 1 page 169

- Rd: destination register

- Rs: source register

- Ra: register that holds address

Moving between registers and memory using LDR and STR, we typically denote address given by register with square brackets. Both takes the destination (for LDR) or source register (for STR) as the first argument, and source (for LDR) or destination (for STR) memory address as the second argument.

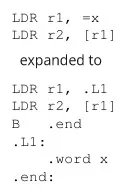

For example, to load a value from an address and store it in register:

LDR r0, =addressLDR r1, [r0]We must do it in two instruction. ARM assembly does not have a single instruction that loads a value from a given memory address directly into a register. Address must be loaded to register first, then the address is actually loaded when moving it to another register.

For a large literal or absolute address, which do not fit in 32 bits, they must be stored in literal pool. It is section of the program that stores data and can be accessed using = sign. It is similar to accessing a label.

Source: Book 1 page 170

Source: Book 1 page 169, 170

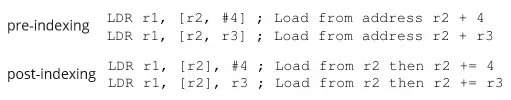

The pre-indexing means that we are modifying the source address before it is loaded, while the post-indexing modifies the source address after the load, both happen before the LDR instruction. The pre-indexing is useful to specify offset relative to the base address, while the post-indexing is useful to specify offset relative to the loaded address.

ARM Arithmetic

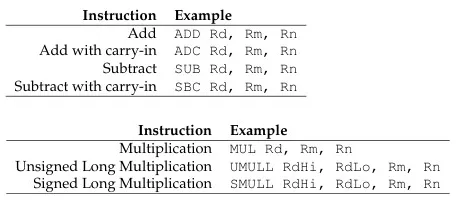

Section titled “ARM Arithmetic”Basic arithmetic are performed with ADD, SUB, and MUL. There are also ADC and SBC to add and subtract with carried value from the register flag.

Source: Book 1 page 171

These take destination register as the first argument, in which it performs the desired operation using the two operands provided in the second and third argument.

Multiplication instruction is different to add and subtract, similar to x86. The multiplication between two 32-bit number can possibly result in 64-bit value, so the result of the multiplication is stored in two 32-bit registers (the RdHi and RdLo).

ARM doesn’t support DIV instruction directly due to its relatively complex operation. Implementing a dedicated hardware unit for division would increase complexity and require more cost. Instead, division is performed by standard library that implement division using other method, typically involving other arithmetic operators and bitwise operations.

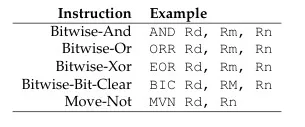

Below is bitwise operations on ARM.

Source: Book 1 page 171

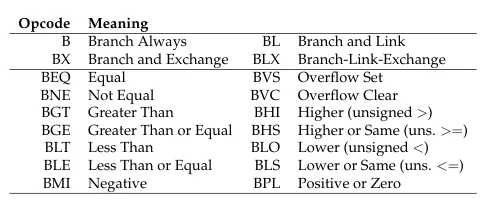

ARM Comparisons & Branches

Section titled “ARM Comparisons & Branches”As mentioned before, result of comparison is stored in the CPSR. It may result in:

- Z (zero): Operands are equal

- N (negative): First operand is less than second operand

For example, when comparing between register and immediate value, we put the immediate value in the second operand:

CMP Rd, RnCMP Rd, #imm

Source: Book 1 page 172

With comparison, we can now construct loops. There are various branching mechanism in ARM. For example, to loop from 0 to 5:

MOV r0, #0loop: ADD r0, r0, 1 CMP r0, #5 BLT loopARM Stack

Section titled “ARM Stack”The stack pointer register is known as sp. Pushing an item, such as register r0 require us to subtract the sp and store (using STR) the r0 into sp.

SUB sp, sp, #4STR r0, [sp]Recall that STR place destination on the right and source on the left. This can be simplified with pre-indexing: STR r0, [sp, #-4]!. sp is added with -4, and the result is also written back to sp (using the !), then the result serve as the destination for r0.

Further, can be simplified into the PUSH instruction: PUSH {r0, r1, r2}

It’s the opposite for pop.

LDR r0, [sp]ADD sp, sp, #4

LDR r0, [sp], #4

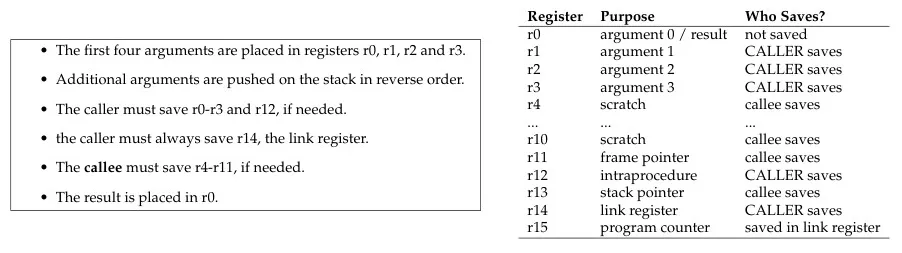

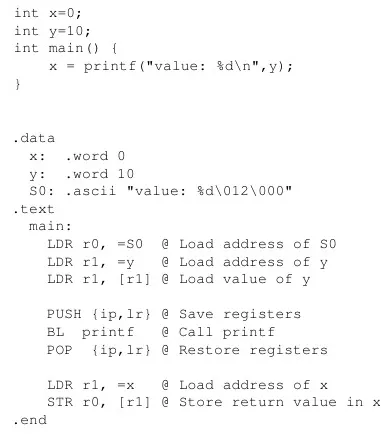

POP {r0,r1,r2}ARM Calling Function

Section titled “ARM Calling Function”ARM describes the convention of calling function below.

Source: Book 1 page 174

Jumping to a function is done with BL instruction. Example of C function and its ARM assembly.

Source: Book 1 page 174, 175